- Home

- Paul Mitchell

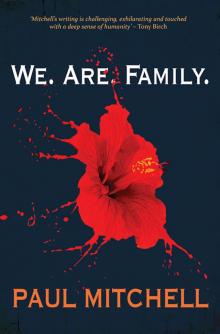

We. Are. Family.

We. Are. Family. Read online

WE. ARE. FAMILY.

WE. ARE. FAMILY.

PAUL MITCHELL

First published 2016 by MidnightSun Publishing Pty Ltd

PO Box 3647, Rundle Mall, SA 5000, Australia.

www.midnightsunpublishing.com

Copyright © Paul Mitchell 2016

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers (including, but not restricted to, Google and Amazon), in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying (except under the statutory exceptions provisions of the Australian Copyright Act 1968), recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of MidnightSun Publishing.

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry is available from the National Library of Australia. http://catalogue.nla.gov.au

Cover and internal design by Kim Lock

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press. The papers used by MidnightSun in the manufacture of this book are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in sustainable plantation forests.

In memory of my grandmother, Shirley Trotter (nee Miller). I can still hear your voice.

We. Are. Family.

1. The Stevensons

Ron Stevenson drove his family back home to Corumbul from Tonvale in his new yellow Corona station wagon. It had adjust-able seating and a push-button FM radio. He pushed a button and the radio changed stations to the one he had preset. A miracle. He wanted to clap his hands but he kept them on the wheel. In the rear-vision mirror he saw his three boys, sitting in the backseat. The eldest, Peter, was staring at the paddocks and the hay bales clumped beside windmills and puddles.

Peter was imagining the paddocks were football grounds. That dark green one, just now, was VFL Park, Waverly. If Ron had known that he’d have turned around and ruffled his son’s hair. The paddocks went on for miles and Peter wondered whether Collingwood could beat Carlton in next week’s semi-final. He hoped it would rain next Saturday because then the ‘Pies would have more chance against the Blues’ famous mos-quito fleet. They would run the pants off Collingwood unless it was muddy. He saw Ricky ‘The Racehorse’ Barham dashing along the wing of a paddock, touching the ball in a puddle then kicking long. As the car took a bend, Peter’s waterlogged footy rolled on the floor.

Ron wore a short-sleeve business shirt and tie. He’d thought he might be able to duck down to the office after the trip. A stupid idea and he knew it. They wouldn’t make it home until after eight because they’d have to stop for fish and chips, or else the kids would be at him and Julie the rest of the way. ‘When are we going to get the fish and greasies?’ they’d whine. The two younger boys, Simon and Terry, were at each other as it was, fighting over a Darth Vader doll. It had a missing foot, but they still wanted it bad. Ron waited for Julie to turn around and barrel them, but she kept her eyes on the highway as if she were trying to stare a hole into the windscreen. She had a bee in her bonnet, he thought. And this one isn’t going to buzz out in a hurry.

It had rained on and off all day. In Tonvale, the grass out front of the white stone building had been smooth like a skating rink. Peter had slipped around, trying to kick his footy. His brothers got amongst it, but they weren’t much fun. They were too little to kick properly, and they just rolled around and tackled each other. Then his dad had joined in.

The last few months, Ron had been busy at work learning how to be the transport company’s branch manager. He’d always worked for them, but this was his first go at the top job. And he was tired out. But he’d felt light this afternoon as he’d dashed around in the drizzle.

‘Good roost,’ he’d said, even when the ball had dribbled off Terry’s sneaker. Ron would have copped an earful as a kid for kicking as shithouse as that. But his old man had long disappeared. So it didn’t matter what he thought. Ron chased Simon and Terry. Just for fun, to keep them on their toes. They laughed and tackled each other all the more.

Peter got sick of his brothers getting all the attention. He walked to the window and looked in. He saw his mum. She was in her white polo neck jumper, talking to a nurse in a chalk blue dress. They were standing next to his Aunty Sheree who was lying in bed. It was the middle of the afternoon and she was asleep already, her scraggy yellow hair spread on her pillow. Next to his aunty were three other beds, grey blankets on them but no one underneath. His mum saw him. She mouthed Go! and shooed him away with a swipe of her arm.

Peter copped an elbow from Simon, who was having another go at getting Darth Vader from Terry’s grip. In the front seat, Julie turned, her voice like a radio without much signal.

‘Stop it you three.’

‘I wasn’t doing anything.’

‘Just shut up. All of you, shut up.’

Ron hadn’t said anything for half an hour, but he knew he was included. The apple cart was already upset and he didn’t want any more fruit to fly off.

Everyone shut up. Then Terry made a grab for Darth Vader’s light sabre. Simon belted him and Terry squealed. Julie swung around and Peter noticed what Ron hadn’t: the red rims of her eyes.

‘Right...’ she said, her voice shaky.

Ron waited, they all did, for her to say, ‘Ronald, stop the car, your sons can walk home!’ But her voice drifted off and all they could hear was the Corona and its highway whistle.

Soon the sky turned rough charcoal like the barbecue when Ron forgot to clean it. Stars queued up quietly on the horizon and Ron saw his youngest two were asleep, their arms and legs in a tangle. He wanted to reach over and touch them, but that was Julie’s job. He kept on with the driving, head down, his mind full of what he didn’t want in it: which trucks were going to come back with gear problems next week, and which tractors were causing dramas at whose farms. The trucking world was a bugger, but he was too short for wood chopping, as his old man had told him. Five hundred times.

No matter where they’d moved, Ron had always made sure Sheree could set up house in the same town as his job. Wasn’t that enough?

The car vibrated and Peter allowed his head to thrum against the glass. He asked himself the same questions he’d asked his parents all day.

Why couldn’t he go into Aunty Sheree’s room today? Why did they take her into the white building? Is it a hospital? Is she coming back home to Corumbul?

They’d all got the same answer: ‘Good boys should be seen and not heard.’

His aunty was lying in a grey bed in Tonvale tonight instead of her own, but no one would tell him anything.

Whenever his mum took him and his brothers to their aunty’s house, Peter was happy. Because that’s when his mum was happy. She got into her flowery dress and a good mood, and Peter skipped beside her on the footpath. He leapt the steps of his aunty’s bricked-in patio and felt a warm buzz when he saw the colours shooting from her glass kookaburra mobile hanging low at her front door.

Ron thought that bloody mobile was a health hazard. His hands were tighter now on the wheel. She’s his sister. And he’s not bloody made of stone. He’s got feelings.

‘What was I supposed to do, Julie?’

He said it loud enough to be heard above the car whistle. Which was really pissing Ron off. It was supposed to be a new car. Julie kept her voice low like he was a waste of her breath.

‘I’m not discussing it now.’

Bugger her. She always decided when they could talk and when they couldn’t. Ron gunned the accelerator. The Corona whooshed and he thought that would be enough to let Julie know he was miffed. But, of course, it was alright for her to talk again, even though she’d just said she wasn’t discussing it. A

nd she didn’t even look at him when she did, just peered at the hills turning black as her mood.

‘Your own sister!’

‘What was I supposed to do?’

Simon stirred and Peter shut his eyes quickly.

‘The kids!’ Julie hissed.

Ron shook his head.

The kids don’t care, he thought.

Peter would skip up his aunty’s patio and past the rainbow kookaburra. Once he got through the forest of fat-leaved rubber plants in his aunty’s corridor, he came to long strings of hanging beads that made a coloured picture of Jesus. He always beat his mum and brothers to Jesus. He smashed both fists into Jesus’ stomach and burst into the kitchen, the beads brushing his face.

Sheree’s kitchen was a wall of cupboards with mesh holes in the doors. Peter thought they were so the food could breathe. Sheree would always be at her table, poking around in the junk from the op shop that she’d spent her dole money on: porcelain cats, watering cans, huge biscuit tins, dusty vases, and big fluffy toys. When she stuck her head out from behind it all, Peter thought she looked like a canary poking out of a clock.

‘Greetings my darlings, my sweet lovelies... Do you want a lolly?’

Peter and Simon always knew better than to take the bait, but Terry didn’t.

‘Yes please, yes please,’ he’d say and Sheree would tell him she didn’t have any.

‘But I’ve got something better.’

One day she pulled from her pile of junk a doll that was plain dumb compared to a Chewbacca. It was a soldier, his uniform dyed purple, yellow and red, and where he should have held a rifle she’d stuck a guitar made of balsa wood. As stupid as it was, Peter had kept it and plonked it on his windowsill to watch over him at night.

When Sheree handed out her presents, her eyes were as big as hubcaps and her bright lipsticked mouth stretched into a smile that didn’t show her teeth. Peter thought her smile looked like a skinny red banana stuck to her face. After they’d received their gifts, Peter and his brothers would go outside and play on the wooden swing set she’d made especially for them. Back when she had a job. The set was painted like a rainbow. Peter would swing back and forward, looking through the window and watching his mum and aunty at the kitchen table. Sheree laughed and waved her hands around and Julie giggled.

His aunty’s house was like a carnival. Peter wished they could all move down the road and live with her. Aunty Sheree would, he was sure, let everyone sleep on the wonky beds in her spare rooms.

‘Why are you only happy at Aunty Sheree’s?’ he’d asked his mum once on the way home. She’d looked at him with squinty eyes and said nothing for a while. Then she’d said he and his brothers were driving her mad with their questions and couldn’t they behave better, more like a yard manager’s sons?

Peter watched his mum grip her handbag in the green light from the dashboard. Ron looked at the bag, too, wondering if it was supposed to be his neck and with one more squeeze she’d get the life out of him. Julie turned to the darkness in the backseat and Peter closed his eyes again.

‘Ron—’

‘I’ve got to head to work when we get back.’

‘Too busy for anyone! Even your own sister!’

Ron took a slow, deep breath. He turned to Julie and was about to let rip but, as always, he couldn’t think of anything to say. He swallowed his anger and it tasted like burnt toast. Julie unwrapped a piece of gum. She chewed so hard on it that Ron thought he could hear her above that damned car whistle.

The sky blackened. Rain splashed Peter’s window and he looked at his reflection in the droplets. He was sure now his aunty would be staying in that bed in Tonvale. For good. He remembered the room they’d left her in, the white walls and the grey beds. He couldn’t imagine what his bright-coloured aunty would do in there all day. The more he churned it, the more he thought it was some kind of hospital. And his aunty was there because he’d dobbed on her.

She’d done a wee in her backyard, holding her pink and orange skirt in her teeth. She was supposed to be babysitting him and his brothers. Peter had told his mum about it that night and she’d said, ‘Don’t worry, don’t think about it anymore.’

Then Julie had told Ron. And Ron had rung the Tonvale Mental Hospital. What else was he supposed to do? He’d told Julie they couldn’t have their kids dealing with that kind of thing. ‘She’s finally lost her marbles, completely,’ he’d added, then turned off their bedside lamp.

After Peter dobbed on her, they didn’t visit Sheree much. And she hadn’t been at her kitchen table the few times they had. She’d been flopped instead in her beanbag in the lounge, surrounded by her hand-made cushions. Sometimes she’d lifted her skirt up and down like it was annoying her. When she’d done that, Peter’s mum had sent him and his brothers out to play on the swings. Another time her church friends were there, praying. A woman in a white dress had made Sheree’s dinner and then done her dishes. The last time Peter had seen Sheree at her house she had been sitting on the backyard swing. She had bare feet even though it was winter. She had smiled then cried, over and over. Her red banana lips had gone up and down like a clown trying to learn how to be in the circus.

Today, Sheree had slept all the way in the backseat, even when Ron had turned up the radio. Peter loved that new ELO song. He’d sung along. Something about a woman, sweet-talking.

He felt bad for singing now.

The window vibrated and Peter’s head nodded against it. His eyes went heavy. His parents were dark shapes in the front seats. Then his mum’s voice.

‘The church people said they’d look after her. You knew that... And me. I could have looked after her. But we couldn’t have that, could we? What would the town say?’

Her breath came in short gasps.

‘And what about when we move next? What happens then?’

Ron went silent for a long time. When he finally answered, the Corona was on the outskirts of Corumbul.

‘She’ll get looked after.’

Ron turned the car down their street. He and Julie didn’t look at Sheree’s house as they passed it. But Peter did. Ron turned to Julie, but she wouldn’t take her eyes off the windscreen wipers. Peter watched them too, flicking back and forth, trying to touch each other but never making the distance.

2. Ron Stevenson

He only knew what everyone else in Laharum knew: The Butcher was the archenemy’s new gun forward. Derrinallum had recruited him from Echuca. Fresh for the ’51 season. No one knew what he looked like because no one in Laharum had clapped eyes on him. He was just chatter around the school monkey bars and whispers in the dark at the flicks. A myth Ron’s older brothers, Stan and Ken, tossed around as they all climbed the elm behind the farmhouse.

They say The Butcher carries two carcasses from his van to his bloody sawdust counter.

The Butcher’s thighs are as thick as a bull’s. Two bulls.

Did you know The Butcher was pissed off one Satdee because Echuca lost so he rammed his shoulder into the clubroom wall and he fell through? Right into the Visitors’ change room? Right in the middle of when they were singing their theme song!

His brothers went on and on. Ron looked down from his perch to the farmhouse and its peeling tin red roof. He wondered if his father was in there, worrying about The Butcher.

Maybe. But Bernie Stevenson was tough as nails that had been banged into a shed wall, gone rusty, and pulled out again. He’d won his division’s boxing title in the war. Ron would hear him puffing as he shadow sparred behind the shed. He’d never seen his father throw a fist in anger, but Ron had copped his belt and the back of his hand. Plenty of times.

His dad was wiry. His arms were better suited to steering cows around paddocks than carrying them dead on his shoulders. So Ron was glad Bernie was Laharum’s centre-half-forward. Because that was the position The Butcher played for Derry. His dad and The Butcher wouldn’t meet on the field. And that was good. Because Ron had been to the Laharum Butchers. He’d seen the

chart on the wall. All the different cuts of beef, marked for chopping up. The Butcher of Derry would have some other poor Laharum Demon on his wall chart, not Ron’s dad.

‘They say The Butcher carries a carcass on each shoulder and loves the smell of blood,’ Joyce McKenzie said as she put the last tin of peaches into a brown paper bag for Ron’s mum, Lynne. It was the week before Laharum was set to meet Derry in round one and Ron was with his mum at McKenzie’s Mixed Business. Joyce was behind the counter, straw hat on as usual. She’d packed Lynne’s apples, pears and bi-carb of soda into paper bags sensibly. But she’d been strangely quiet before her outburst.

‘It’s just Derrinallum trying to stir us up, Joyce,’ said Lynne.

She pulled up the flap pocket on her big floral dress and grabbed out her purse. She gave Joyce her shillings, smiled and rearranged her brown curly updo.

‘Well, good luck to Bernie. Glad my Howie’s not playing...’

According to Bernie, her Howie couldn’t kick over a jam tin. Lynne huffed and didn’t say goodbye or thank you. She dragged her bags and Ron to the door. The shop bell rang them out and they chugged back to the farm in the 29th Anniversary Buick. Ron was embarrassed to be seen in that car. It didn’t have a roof. Everyone’s car had a roof for God’s sake.

He asked his mum if she was scared of The Butcher.

‘Ronald, sit back in your seat and keep quiet will you?’

He was a church mouse all the way back to the farm.

The Derrinallum Kangaroos had won the 1950 Horsham Dis-trict Premiership. They’d played Laharum in the Grand Final and beaten them by 62 points. They’d slammed the Demons into the brick-hard oval time after time. And they’d won the punch-up on centre wing in the third quarter.

We. Are. Family.

We. Are. Family.